This begs for an answer: Can an author and extreme philanthropist be so consumed by continually giving, building and endorsing, that his own craft dies a slow, unassuming death? Or is generosity to other artists, the tendency to embrace the potential of the other – just a journey towards the realization that one’s own work leaves much to be desired and is essentially mediocre?

I wish I’d come to know Stan Leventhal’s work just a few years earlier than 1999. It might have been remotely possible to contact him, to document his artistic process or at least – get a sense of his life and times first hand. I first came across one of his last works, Skydiving on Christopher Street at a thrift bookshop in Vasant Vihar. I had the least intention of buying a book that evening, let alone a paperback semi-autobiographical by a gay pornographer, but in retrospect, it was probably written (pun absolutely intended).

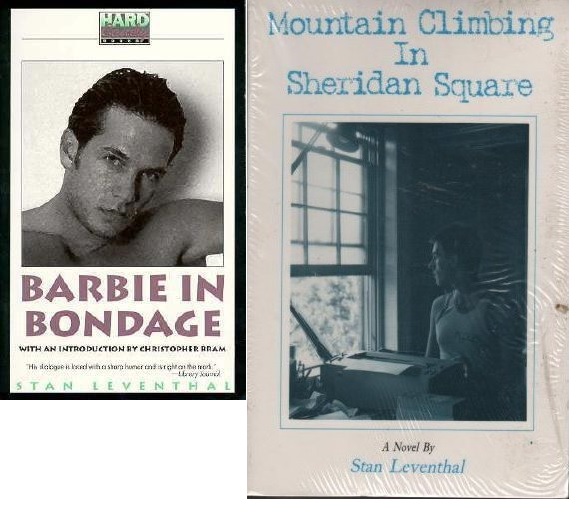

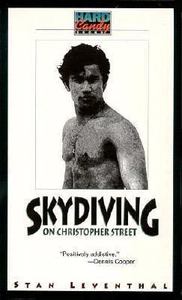

The cover leaped at me right across the moldy stacks of used Enid Blytons, John Grishams and Mills & Boons. It was wrapped in plastic and taped to make it appear like it was fresh out of the press. The cover had a treated, grainy, black and white image of a male model, presumably blinded by the sun just before the photographer’s click. The appeal, for me, was in the solid charm of the absence of colour, an air of antiquity and the suggestiveness – that this one might hold details that didn’t quite make it to mainstream pulp. Yet, the name of the publishing house, Hard Candy, was discreetly printed in neon blue and pink, right on top. A little endorsement by a Dennis Cooper that said, “Positively addictive” and the convincingly written testimonials at the back cover assured that this would be an interesting read at the least. That the book would also partly document an important time in the history of gay politics – dealing with H.I.V, formerly known as G.R.I.D (Gay Related Immune Deficiency) and ACT UP, the aggressive movement against the stigma through the eighties and most of the nineties as well. The most apt description was by Michael Bronski, author of Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility –

“Like Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man, the book relies on plain-spoken language to convey the multiplicity and depth of lived experience.”

“..an insider’s view of the porn industry adds a comically surprising dimension.”

– said Sarah Schulman, also an author, historian and playwright and as I later discovered, closest friend of Stan’s.

I picked up the only copy in the shop for a modest 180 rupees, and took it home with the promise of an edgy, introspective and engaging read that could leave me reeling through at least the remainder of my teenage years, the generation (at least in India) that was so firmly and hegemonically blindfolded from any gay literature, images or the least references. It was a miracle that a provocative drama like Philadelphia had made it to video stores like Music World and Planet M…or that Deepa Mehta’s Fire got a troublesome but successful run in the theatres. Could it be that most people didn’t know or care to find out what it was based on?

“This book is dedicated to the loving memory of Bobby Nolen Locke, forever and always.”

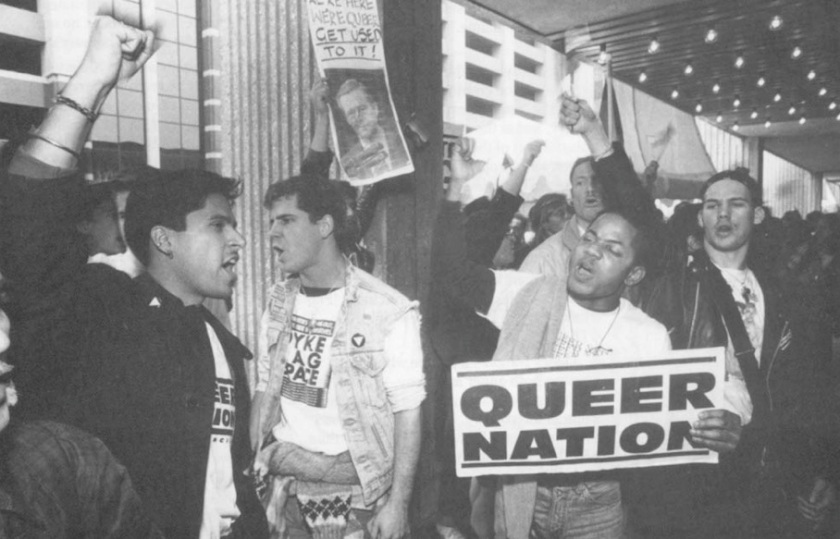

There is little chance now, of finding out who Bobby was, but upon reading the book, it could be one of the many loves of the nameless narrator in the book – Jon the Broadway star, Lenny the author or Eric the computer hardware salesman, who he seemed to have settled down with. While the book turns to the romantic episodes with most lovers lost to A.I.D.S for comfort and assurance, it honestly and effortlessly reveals a strong, pleasant and mostly enterprising man sensitive to the needs of the world around him and a milieu seemingly defined by a dichotomy – of easily accessible outlets for sexual minorities on one hand, and the politically-motivated opposition thereof.

Stan’s protagonist is an aspiring author in New York’s teeming Christopher Street, one of the crucial mapped areas of its time. Failing to have met adequate success, he makes ends meet as an editor in a porn publication firm that offers something for both gay and straight readers. He lives with his lover, a Broadway understudy in a state of discontent. Clearly, the pressures of a falling career graph, an indifferent partner, being H.I.V positive and hostility on the streets of New York forces him to look to the past loves and the painful, but sheltered childhood spent in the American Midwest. The comic relief to the intense, non-linear narrative comes from the dimwit, ignorant management in his office, sardonic conversations with his best friend Dana (who is a lesbian lawyer) the politics of censorship and the many embellished anecdotes of dealing with porn stars, most of whom seem to be in for the money and the drugs.

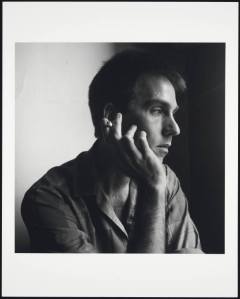

And what do we know of Stan’s real life? As little as this: He was born in 1951, was a three-time Lambda Literary Award nominee and worked as an editor on Mandate, a gay pornographic magazine. We know he was H.I.V positive and suffered a painful death in 1995, as his friend Sarah Schulman amply enunciates. Specific dates for other important chapters of his life or a comprehensive biography are not to be found anywhere online. In a charmingly tragic fashion, his bibliography is the sole publicly available document on his life and work.

I can testify as one of his readers that Stan’s literary sensibilities are in no mood to set trends, redefine prose or narrative. The honesty, the flair for engaging dialogue (both with the reader and between the characters), and a remarkably positive attitude are what make his work engrossing and important. As Dennis Cooper puts it –

I can testify as one of his readers that Stan’s literary sensibilities are in no mood to set trends, redefine prose or narrative. The honesty, the flair for engaging dialogue (both with the reader and between the characters), and a remarkably positive attitude are what make his work engrossing and important. As Dennis Cooper puts it –

“Generosity, evenness, fairness to the reader, sensitivity – these are qualities that most contemporary writers take for granted or overrule with stylistics. In Leventhal’s writing, they not only stand out, they’re positively addictive.”

No wonder then, that I still pick up my copy of Skydiving when I’m ill, when I want to pry on cackling conversations between close friends, when I want to find lost loves that easily assume the form of Stan’s own artfully realised characters, when I want to experience the strains of working for a corporation brushed off with humour, or simply revel in the human condition staged in a modern metropolis.

It was no art, perhaps, but I wouldn’t hesitate to deem it as important work. The musings of a well-informed, sensitised and active citizen wading through the decadent, yet plummeting conditions of New York in the 1990s. Change makers, even aside from Harvey Milk were aplenty, Broadway hits like Rent celebrated Bohemia and politicians fought their most deeply human impulses to emerge powerful, minorities were attacked at the slightest democratic provocation and fear of the misunderstood H.I.V outbreak determined people’s political stand itself. Stan worked safely and effectively within the system to make right whatever little he could, much like the restrained candor of his books. Sarah Schulman recalls in her essay “Through the Looking Glass” –

“All of his books are out of print now. And the harsh truth is that Stan never really became a great writer. But he wanted to be. My favorite story of his was in the final book published in his lifetime, Candy Holidays and Other Short Fictions, where Stan remembers the last man he unknowingly infected. However, Stan was a great friend. He liked to have a Jack Daniels and a cigarette; he took AZT with bourbon sometimes. A tall skinny guy, clean shaven with short brown hair, he was kind of a hippie, wore a jean jacket, T-shirt and had a backpack. Stan read everything and was one of the first men I’d met who actually read lesbian fiction and loved it.

He lived in a filthy apartment on Christopher Street overlooking the park. It was packed with books and CDs, his guitar and TV. He’d come to the city from Long Island to be a singer and started out on the folk circuit. He’d broken up with the love of his life right before we made friends and plunged himself into the creation of Amethyst Press, which probably published the most interesting collection of gay male writing in the history of our literature. He published books by Dennis Cooper, the late Bo Houston, the late Steve Abbott, Kevin Killian, Patrick Moore, Mark Ameen-all important, under-appreciated artists. After working at porn magazines like Torso for years, Stan had a formula. He’d publish a highly intellectual, formally innovative novel by a gifted writer and then slap a piece of beefcake on the cover so it would sell. His favorite writer was Guy Davenport, to whom he’d written a comprehensive and adoring monograph.

Near the end of Stan’s life, Amethyst got wrested away from him in a power play, and then the new bosses destroyed and folded it. This depressed him deeply; he was filled with anger. I remember one lunch at a Chinese restaurant when I saw tears splash into his food, only to look up and discover it was sweat; he had such a high fever but was still running around. His true love died. My final visit to his apartment, the place stank. The toilet bowl was black and there were no sheets on the bed. Stan gave me one of his books, Resurrection of a Hanged Man by Denis Johnson, which unfortunately I didn’t care for. I was surprised, actually-usually we agreed on books.

I saw him in Beekman Hospital the week that he died. He was bald and shaking, could barely sit up, but did. That was the first time I met his mother, Pearl, an old uncomprehending woman. “There’s so much to say,” Stan told me. Then he told me something I won’t repeat here. I stepped out into the hallway as the doctor fiddled with his body and Pearl followed. “Stanley always wanted a hard cover,” Pearl said. Then he was dead. Stan’s best friends were Chris Bram and Michelle Karlsberg. Later Michelle told me about her final conversation with Pearl.

“Should I ask Stanley if he wants to be buried in Florida?” Pearl asked.

“Stan doesn’t give a shit where he’s buried,” Michelle told her.

Like all the dead and the living, I think I see him everywhere. But it is just new versions, young versions of guys like Stan. Most of us seem to be re-created every fifteen years. I see a twenty-year-old me almost once a month, and a twenty-year-old, forty-year-old, sixty-year-old Stan passes by on the street often enough.

This good man who was a loyal friend, who had impeccable taste in literature, who started a literacy program at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center to teach gay people how to read, who has a library named after him, who published some of the most important gay male writers of our day-this guy could not really write. I feel guilty saying that because I know how much Stan wanted to be a great writer. But on the other hand, one of the paradigms we’ve created about AIDS is that of the dead genius. And of course, most of the people who died were not great artists. They were just people who did their best or didn’t try at all. Some of them were nasty and lousy, others mediocre. Some knew how to face and deal with problems, others ran away and blamed the people closest to them. Stan was unusual because he gave so much to other people, both personally and in his never-ending contributions to the community. These actions alone make him exceptional. But as an artist, he had, as one colleague put it “an ear of lead.”

If his work were to introduce his being to us in a moment that encapsulates the leading man of his book, it would be this following excerpt that captures an amusing moment at work, yet reveals his disdain for and embracing of life – all at once:

The intercom buzzes me back to the cold atmosphere of my office, my desk strewn with memos and red felt-tipped markers, the photographs on the walls of naked men posing and flexing. Rita informs me I have a visitor. I glance at my calender and see no appointments listed. She says his name is Steve Harris…he’s wearing a polo shirt and acid-washed jeans. There is an eager look in his eyes.

“Can I help you?” I ask.

He introduces himself and claims to be the person who sent a resume and phoned earlier. Now I recall the name.

“You’re looking for a job?”

“That’s right.”

“I told you we don’t need anyone right now.”

“I thought if we met you’d see how intelligent and reliable I am and you’d remember me when you do need someone.”

“I’ll keep you on file, ” I reiterate, “and call you for an interview should I need you.”

Suddenly, he fakes a move to the left, then runs past me down the corridor. Rita looks up from her tabloid.

“Should I phone the police?”

“Not yet,” I say and take off after the weirdo running down the hall who pauses to look in the offices with open doors. As he passes, heads pop out and turn to watch the intruder who has transformed our ordinary, dull corridor into the multi-coloured, flashily lit alley of a pinball machine.

“What the fuck’s going on?” I’m asked as I scurry past a bewildered accountant. I ignore the question and continue the pursuit. I find Steve Harris standing, staring at an autographed, life-size, nude, full-colour poster of a deceased porn star. Mr. Harris looks like he’s about to start drooling. He grins at me. “Gee, it must be great working here, getting to meet people like Ben Dover!”

“I never met him.” I say, as a crowd of art assistants and subscription clerks gather.

“You never met him. Why?”

“Well, for one thing he died before I even started working here.”

Mr Harris’ face seems to collapse, as though someone had dropped a telephone book on his head.

“But I thought…”

“You thought working here was like being invited to a fabulous gay orgy every day.”

“Something like that.”

“Look,” I say with sympathy, “you could have more fun working at Burger King.”

I take Mr. Harris into my cubicle and show him my typewriter, computer terminal, file cabinet, telephone and Rolodex. I walk Mr. Harris to the reception area. There are two officers standing by the desk. I press the elevator button. The door opens immediately and I push Mr. Harris past the sliding door and wait until it closes before turning to the police officers.

“What can I do for you gentlemen?”

“Report of a disturbance, says the heavier officer.

“Vagrant wandering the building” said the skinny one.

“I don’t know who put in the call, but I apologize for the inconvenience.”

I give them the grand tour, during which the heavier officer openly enjoys the sight of big-breasted women adorning the art department walls. Before escorting them back to the elevator, I offer them some free samples. The heavy officer eagerly accepts but the other guy declines as thought I’d offered him a glass of poison.

Incidentally, while I get in touch with Sarah Schulman to unravel more on Stan’s life and gain any possible leads to adapt his book into a potential film, the last advertorial page in the copy pleads the reader to call a 1-800 number that probably doesn’t work anymore, and indulge in phone sex with lonely, aroused New Yorkers.

I was an old, childhood friend of Stan’s. He changed my life in many ways. He introduced me to different forms of traditional American Music and dance which are still a major part of my life as well as the way I make my living.

That’s wonderful to know, Mitch! I might write you sometime to talk some more about this, if that’s okay.